Anna Eyjolfsdottir interview: Paradise Lost (2013)

artdesigncafé - art | 20 December 2013

This article-interview was previously published in Sculpture magazine, 32(5), pp. 39-43 in June 2013.

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. LEFT: Black, (2007). Aluminum, wood, plaster, toys, cage; variable dimensions. RIGHT: White, (installation detail) (2007). Bronze, plaster, toys, found objects; dimensions variable. Both works installed at Start Art Gallery, Reykjavik. All photos courtesy of the artist.

Anna Eyjolfsdottir: Paradise Lost

In 2000, Anna Eyjólfsdóttir, president of the Reykjavik Sculptors’ Association, invited me to cover a couple of sculpture exhibitions celebrating Reykjavik as the European Capital of Culture. In the following years, this city of 120,000 witnessed a remarkable building boom. But times change, and Iceland soon fell victim to 2008’s devastating economic bust, its crisis covered extensively in the international news. These events are key subjects in Eyjólfsdóttir’s work, revealing an underside to the “idyllic Iceland” experienced by visitors, like me, who come for its natural beauty or its contemporary art and return home with magical memories.

Over the past 20 years, Eyjólfsdóttir has had solo exhibitions in small museums, art centers, and private art galleries in Iceland, Finland, and Denmark. She has also participated in group exhibitions and given performances in the Czech Republic, Germany, Greenland, Lithuania, Spain, and Sweden, and she presented at the Art on Armitage window gallery in Chicago. Eyjólfsdóttir studied fine art at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany and earlier at the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts in Reykjavík. Born and raised in Iceland’s capital, she continues to live there today.

The following are excerpts of my interview of Anna Eyjólfsdóttir.

R. J. Preece: Could you explain your installations Black and White? Why is the rearing horse attacking a baby, and why are the Barbie dolls escaping from a gilded cage? Is this a comment on Icelandic society?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: Both of these installations refer to life in Iceland. Black is a symbol for those who are bound and unfree, trying to escape— in this case, from a gilded cage— even at the cost of their lives. Barbie is a role model who shows what is expected of women: “Shut up and be cute.”

The rearing horse is made of aluminum and is a symbol of power. It represents, in part, the aluminum companies whose factories contribute to the destruction of Iceland’s wilderness. The horse stands on top of a burnt dresser with partly open drawers, while its front legs rest on a white plaster sculpture of a baby that represents innocence.

White, on the other hand, is about love, the communication of children and nature, games, and abundance. Here, the horse is made of bronze, a reliable material that mankind has used for ages.

Together, the two works are a comment on abuse— a worldwide problem that Iceland has not escaped. White refers to a news story about an Austrian girl who was imprisoned in the basement of her house by her father.

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Harmony, (1994). Iron, rubber aprons used in fishing industry, cassette, audio; 208 x 50 x 330 cm. Installed at Reykjavík Art Museum. Photo: Kristján Pétur Guðnason. Sound piece plays voices and machine sounds from a fishing industry plant.

R.J. Preece: In your outdoor work Harmony, you hung aprons from a stand, accompanied by sounds from a fish factory. I understand that working in this industry, which is the economic backbone of Iceland, is now considered undesirable. Do you see Harmony as nostalgic or critical of this perceived undesirability?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: It’s definitely a social piece. If I weren’t an artist, I’d probably be in politics. I think that we as Icelanders should be proud of our fishing industry. Harmony is dedicated to the people who work on the conveyor belts in our fish processing plants. They have a life outside of work and let themselves dream. It turns out they are thinking about anything other than fish while they work.

R.J. Preece: Could you explain your earlier work, Wheat field (1997), which is about Icelandic women?

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Harp, (1991). In memory of the eruption of Hekla. Wood salvaged from an old pier and grass seeds, 6 x 3 m high. Installation and performance in two parts— first on the Reykjavik coast, here the artist has sets the sculpture alight, and a second intervention at the base of Hekla.

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: Wheat Field refers to the Viking settlement of Iceland in the 9th century, which included very strong Viking women. I made a figurehead— like for a ship’s prow— out of driftwood. It represents the first women to arrive in Iceland, carrying a sword in one hand and a white bird in the other. I placed the figure in the middle of a circle of plowed earth planted with wheat, which grew during the exhibition. This symbolized the role played by women in creating the future of a new place.

R.J. Preece: Could you tell me about Harp (1991)?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: This was one of my final projects at art school; for me, it was the beginning of my art. I set fire to a harp-shaped wooden sculpture, which was placed on the coast of Reykjavik. The title refers to the sounds one hears from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. I put some of the ashes from the fire into a hollowed piece of wood— another phase of this sculptural performance— and planted grass seeds in the holes. Then, I took the piece to the foothills of the volcano Hekla, which erupted in 1991. In this way, I could do my bit to heal the land and the volcano.

-

Anna Eyjolfsdottir. Signaling Coastline (2000). Flag poles, ships‘ signal flags; 600 x 3600 x 120 cm. Installed at Reykjavik Harbour as part of outdoor exhibition: Coastline 2000, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photo: Helgi Hjaltalín Eyjólfsson. The 17 ship-signaling flags spell out “Coastline” in Icelandic to ships that approach the land.

R.J. Preece: Could you explain your work in the “Coastline 2000” public art project and what it aimed to achieve?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: In addition to making a piece that I felt worked in aesthetic terms, I wanted to use the opportunity to create something that could be viewed from either land or sea.

For years, I had wanted to send a work out to sea. Sailors rarely have an opportunity to enjoy art, but when you talk to them, they are interested and have opinions on what artists are doing. When I was collecting the signal flags, I talked to a lot of skippers— they were very helpful, finding flags and explaining their significance. Despite all of the technology that we have now, every ship is still kitted out with signal flags. They represent letters and numbers, and anyone can learn to read them. They can be read from the shore even before a ship is docked.

R.J. Preece: Most visitors to Iceland don’t understand that it can be a difficult place to live: it is isolated, the population is small, and the politics of daily life can be intense. So, some people are going nuts, fighting in boxes. Is this what a lot of your work is about?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: You are right that people don’t get a real understanding of life here from just a short visit. I am sometimes ready to explode, though no one would notice. I sometimes feel as though I’m always struggling with myself, and this probably shows in my work. Sometimes I feel like a lion in a cage. Most of my pieces are based on current events. I get my ideas from the news, Icelandic and international.

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Think for Sink (2006). Foundation: varnished, carved wooden table; porcelain sink; plates; 90 x 100 x 60 cm. Installed at Living Art Museum, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photo: Símon Hallsson.

R.J. Preece: In Think for Sink, you combine housework, traditionally women’s work, with a kind of monumental form. The presentation is soothing, with its polished surfaces, but there also seems to be a tension in the juxtaposition.

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: In this piece, as in Harmony, I was thinking about repetitive jobs that sometimes bring about a meditative state. I wrote in oil paint on the plates, which I then placed in a sink. The sentences recorded my personal thoughts, or stored memories, which no one can take away from me. It would take a long time to read them all; and some were hidden— you could see many of the messages from above, but not all of them.

R.J. Preece: You also use coat hangers in a number of works. What attracts you to them?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: I started using wire hangers because they can be found everywhere, and I like to use common materials. I started by experimenting with little sculptures made from hangers and other materials, such as pantyhose, paper, and whatever I could find lying about. I’ve used many crates of wire hangers to make pieces; for me, these wire works serve the same function as sketches do for other artists.

-

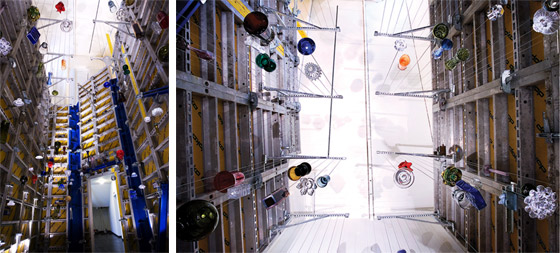

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Power (two views - details) (2006). Three-part work. One part: Construction moulds, iron, found glass object, tailcoat, hat; 810 x 720 x 450 cm. Installed in group show Mega vott, Hafnarborg Museum, Hafnarfjörður, Iceland. Photos: Stefán Þ. Karlsson.

R.J. Preece: Could you explain Power, a three-part installation that you made for the Hafnarborg Museum in Hafnarfjörður? I’m particularly interested in the section that employed champagne glasses.

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: I used champagne glasses because we drink champagne when we celebrate. But the glasses are empty, so the question becomes whether the celebration is about to begin or has already ended.

In 2006, after a two-month stay in Nigeria, I came home to the gold-rush mentality of Icelandic society. New districts with glass-fronted buildings, building cranes, and concrete mixers were everywhere. I felt that it couldn’t be real, and I used to ask, “We must be on the way down because this cannot be reality, right?”

No one was interested in this question. The president and the government were busy praising the bankers and the financiers.

R.J. Preece: Power also includes hanging glass objects. Could you explain how you were commenting on consumerism in Iceland?

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Power, (detail) (2006). Three-part work. One part: Found objects, bamboo, earth; 170 x 350 x 300 cm. Installed in group show Mega vott, Hafnarborg Museum, Hafnarfjörður, Iceland. Photo: Stefán Þ. Karlsson.

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: The first thing I knew about this piece was that I wanted to use Doka supports, which are popular in the construction industry because they speed up the process of casting concrete. I also wanted to tackle the space in the museum. I wanted to build something that made use of the high ceiling. I was also thinking of what I had seen in Nigeria and what I was confronted with when I came back to Iceland. The glass objects were selected from a large collection that I have and sometimes use in my works. The space became like a chapel with a large entrance.

The third part of Power, which was installed under the stairs, referred to my time in Nigeria and involved a contrast between rich and poor. It consisted of empty ceramic plates, cups, and food containers on a dirt-strewn floor, along with bamboo canes propping up other objects. Using the space below the stairs symbolized how many Nigerians are marginalized by outside forces, as well as by Nigerians in power.

Outside of the construction, I hung a tuxedo and a hat, ready for anyone who wanted to change roles and celebrate with champagne.

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Paradeisos, (2002). Concrete slabs, glass, sand; 30 x 2500 x 1000 cm. Installed at Reykjavik Art Museum – Hafnarhús. Photo: Vigfús Birgisson.

R.J. Preece: Could you explain the contrasts presented in Paradeisos?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: Paradeisos is installed in a courtyard at the Reykjavik Art Museum’s Hafnarhús (Harbour House) location, which looks strangely like a prison interior.

With this work— the title means “within walls”— I’m referring to the traditional walled courtyards of ancient Greece. I started to think about how people who had to work in these courtyards (within the walls) might feel and how the courtyards are like prisons. I wanted to build a low-maintenance “garden,” a place for everyone to enjoy, whether they come inside and walk around or look down from above.

The glass in the center of the space reflects the sky like a pond, ever-changing like nature itself.

-

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir. Golden Swans and Dimmalimm (a young princess), (2004). One installation consisting of video, video monitors, two chairs, three photo-works, bandages, artist-made plastic sculptural objects, and plinth. Installation view; dimensions variable. Installed at Reykjavík Art Museum - Kjarvalsstaðir. Photo: Inger Hellen Bóasson.

R.J. Preece: Could you talk about the main themes of your multi-part installation Golden Swans and Dimmalimm (a young princess)?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: The three golden swans symbolize those who have power because of their position, money, or connections. They come together and make plans, often at the expense of those with less power. They feel safe in the group, which is the case with most gangs, political parties, families, and institutions.

Another, solitary swan stands at the edge of a circle. Right now, he is guarding the innocents inside the circle, but everything could change in a moment.

At the opening, there was a performance with two children reading from a fairy tale by Muggur, an early 20th-century Icelandic artist. The story is about a princess who sees a swan on a pond in the palace gardens and comes to visit it every day. One day, the swan is gone and the princess is crying for it when a young prince appears. He explains that he was the swan— under the spell of a witch. He asks her to marry him, she says “yes,” and they live happily ever after.

The apple is the “forbidden fruit.” There are many who want to get the apple and give it to a woman. It is the beginning and the end of so many things and should not be too easy to reach.

The scrotum-like cloth piece is made from royal blue velvet and topped by a phallic symbol. This is a double-edged sword, made powerful by nature, but on which nature also places much responsibility. Is it the downfall of those who misuse their power?

The three photo-based works depict traumatized people partially wrapped in bandages. They are the victims of those wielding power. The three panels represent a sort of communal healing process. They express a hope for recovery and a better world.

R.J. Preece: Whose work— past or present— would you describe as an influence?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: My own life and my immediate surroundings have had the most important influence on me. Artists such as Joseph Beuys and Erwin Heerich have also been important to me— Beuys, in particular, for his experimentation with materials and emotion and Heerich for his Minimalist approach to space.

R.J. Preece: Since the financial crisis, what has been learned in terms of life and art?

Anna Eyjólfsdóttir: I have learned to trust my own intuition. I saw the crisis coming and had constant worries and tried to prepare for it, but all in vain. It didn’t touch me directly because I had no stocks or companies to lose. We live in a country where disasters— natural and manmade— come and go.