Mark Pimlott: Crossing the line (2001)

People have accused him of avoiding commitment, but Mark Pimlott can’t imagine confining himself to a readily definable profession. Trained as an architect and artist, the London-based Canadian inhabits the territory where art meets design.

artdesigncafé - design | 2 August 2010

This article was previously published in Azure magazine in September/October 2001, pp. 115-20.

"People think I’m a bit of a dilletante," says Mark Pimlott, a Montreal-born, London-based artist/designer whose work straddles the boundary between these two professions. Like others working in this grey area, Pimlott creates work that’s difficult to categorize. Trained as both an architect and an artist, he was one of two design co-ordinators for the Starck-designed Ian Schrager hotels in London, and his practice has included painting, sculpture, furniture and interior design, and architecture–as well as writing, photography, and filmmaking.

Art or design? Design or art? Mark Pimlott’s recently completed commissions are on a pivot between the two: A public artwork consisting of party lights installed underneath a Birmingham overpass; a private residence’s large, chic garage that moonlights as a drive-in disco for the owner and his friends. And his current obsession? Executing La Scala, a minimalist and mediagenic stairway to heaven that will face the sea— and serve as a magical stage for a Welsh town.

-

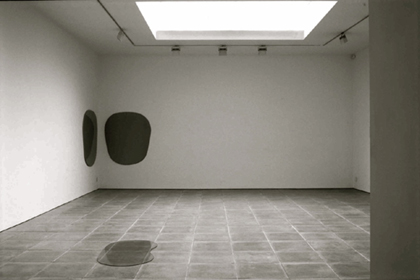

Mark Pimlott. Pool (foreground) and Boue, (both 1996). Installed at Todd Gallery, London. Gloss-lacquered mdf, two parts: 1500 x 1100 x 12mm. each.

In his London studio-residence with a wraparound city view, Mark Pimlott discussed his practice. We were surrounded by classic designs and art objects. Tables and chairs by Eames, Magistretti, Bertoia, Colombo, and others; bookcases by Rams. Philippe Starck’s banquet seating—nicked from the St. Martins Lane hotel trashbin and transformed into a daybed. Some of Pimlott’s own creations also grace the space. They include Boite (1992), an object which looks like a cross between an open box and an abstractly depicted child, and Pool (1994), a piece of glass from a vanity tabletop that now rests on the floor, creating the illusion of a small clear pool of water.

-

Mark Pimlott. Guingette (detail), (2000). Installed at Birmingham Mailbox. Zenon-filled lamps, compact fluorescent lamps, acrylic/ polycarbonate globes, proprietary fittings, and cabling, overall site 54 x 34 x 4.4–6.2 meters.

These earlier works are artwork with almost a capital A. However, his recent commissions blur the boundaries between art and design. Guinguette (2001), a “party-zone” art installation under a Birmingham overpass, counters the modernism-gone-mad atmosphere beneath the city centre’s ring road, a perceived zone of crime and hostility. Mark Pimlott’s design was the winning entry in an invited competition sponsored by developers of The Mailbox, the largest commercial development currently under construction in Britain, with mixed-use spaces for retail, offices, a hotel and residential housing. The party zone acts as the Mailbox’s entrance from the city centre.

In his attempt to "reclaim a part of Birmingham which is no longer considered legitimate," Mark Pimlott was inspired by country inns that used to exist on the edges of Paris, near the city gates. "Quite often they would be close to the city’s fortifications, which by the nineteenth century were earthen ramparts with very wooded areas adjacent to them," he says. "The guinguettes were outside the City of Paris’s jurisdiction—they weren’t taxed in the same way, or subject to the city’s laws. People could go and have a good time there, untroubled by the gendarmerie. I thought I could basically transplant that idea to Birmingham and invert the space from a negative into a ridiculous positive." His installation is composed of crisscrossing strings of party-style hanging lanterns, programmed so more of the fixtures will turn on as the day progresses. At night, Guinguette’s in full party mode.

-

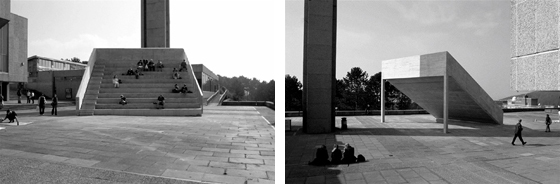

Mark Pimlott. La Scala, (1999-2003). Reinforced concrete, 10 x 9 x 6.1 m. Installed at University of Wales, Penglais campus.

Across the Welsh border in the seaside town of Aberystwyth, Mark Pimlott’s La Scala is scheduled for completion in 2002. "A monumental staircase completing a 1960s civic vision," is how Pimlott describes it. Like Guinguette, it was commissioned for a despised space—in this case, a 1960s brutalist plaza on a University of Wales campus. Bordered on three sides by a library, an arts complex, a student union and a campanile-like structure that is in fact a giant duct for the university’s boiler room, the site overlooks the town, the surrounding landscape, and the Irish Sea. "In my work, I’m interested in the notion of recuperating a period of history of places which have been discarded by people and forgotten. I wanted to make a powerful figure on the piazza—as powerful as those which would have existed in the Italian Renaissance," says Pimlott, ambitiously. "La Scala will just become part of the furniture. It’s an enormous, useless thing that will be used and mis-used by people in a variety of ways—as a shelter from rain, a place for parties, to lie and sit on, get a suntan, to look out at the sea."

-

Tony Fretton. Red House on Tite Street, London (2001). (Studio Mark Pimlott, interiors.) Photo © Hélène Binet.

Even when he is designing interiors for a private residence, his work can have the surreal quality of a gallery installation or a film set. Recently, a young, wealthy collector of contemporary art commissioned him to add colour, history and camp to a new, five-level residence in London, designed by architect Tony Fretton. "It has long been my thought that the world of actual things is a mask for the world of intentions; that representation is all around us; that our world is the consequence of ideas partly articulated," says Pimlott. "The house was a working model for this situation." In Fretton’s Miesian, glass-walled dining room, which projects into the back garden, Pimlott installed a dropped ceiling–a linen sheet, stretched taut and painted with lines that suggest the warp and weft of a fabric canopy. To him, the interwoven threads on the ceiling are symbolic of many different historical strands, including the pre-architecture of the temple, Mies van der Rohe’s pavilion-like structures, and memories of picnics in the country.

One of Mark Pimlott’s strategies on this project was to transform "rooms where guests are alone for short periods of time" into fantasy environments. The “space-age toilet”— one of two small bathrooms off the austere foyer— is a case in point. Pimlott designed the futuristic, mirror-polished stainless steel and Corian washstands and the wallpaper, which appropriates the pattern from a screen saver on an old Macintosh classic of the sky at night.

Mark Pimlott’s design gets a little glam in the bar with its sparkling mirror and lacquer, smoked glass, and an outrageous custom-designed sink shaped like a champagne bucket. And then there’s the “party room” garage, which might make Saint Corbusier roll over in his grave. Beneath a ceiling covered in reflective white plastic, milky white Belgian tiles on the wall disappear into a haze, while funky drooping light fixtures project an apple-green glow. "It’s a ballroom for automobiles," says Pimlott. "I imagined the client driving his Maserati into the space, and having the feeling that he had arrived."

-

Left: View of the dining room into the garden. Painted ceiling by Mark Pimlott. Right: View of third floor bathroom into the courtyard.

Why did this Montreal-born-and-raised visual artist leave a promising architecture career and settle in the English capital? After graduating in architecture from McGill, Mark Pimlott practiced in Montreal with Peter Rose, first designing kitchens and then ultimately a house which was widely published. But something pulled Pimlott across the pond to Britain. "A series of mistakes is the best way to describe it," he says. "You see, I thought I was moving to Europe," he jokes. "As a teenager, I went to Rome on vacation, and I knew for me, the Continent was ’home’. I vowed to come back." When he did eventually cross the Atlantic again, however, it was to study at the Architectural Association in London.

Upon completing his AA diploma in 1985, Mark Pimlott worked for British architects Jeremy and Fenella Dixon. The trio designed London’s Tate Gallery restaurant, entered the competition for the National Gallery extension, and were commissioned to design an imaginary chateau in Bordeaux, a hypothetical project which resulted in an exhibition of works on paper at Paris’s Pompidou Centre. As well, Pimlott was part of Jeremy Dixon, BDP, the team responsible for alterations to the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. At the same time, he was in partnership with British architect Peter St. John (now of Caruso St. John), and the two won a prize for their design for the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts in New Delhi, India. However, all was not yet set. "Through a series of complicated circumstances, I ended up leaving architecture practice entirely," Pimlott says. "The more Peter and I worked together, the more I became interested in working with ideas which weren’t specifically architecture. I wanted to deal with them more immediately. So, I decided to do art." As a result, Pimlott then pursued an MA at London’s renowned Goldsmiths College, the school where many world famous young British artists studied. Since graduating in 1992, he has exhibited in London, Glasgow, Rotterdam, Kiev, Toronto, New York, and recently, Cairo.

Although interdisciplinary work is Mark Pimlott’s natural inclination, he acknowledges that in practice it can be risky business. "I don’t know if this is especially true in Britain, but when you are crossing fields, you are distrusted–you are perceived as someone who will not commit themselves to any formal practice. Whereas in fact I feel very committed to all the forms of practice that I’m involved in, and I’m committed to the discourses surrounding these practices," says Pimlott. "It’s not easy, but I must say I have to work this way because it involves those different fields. It can’t be any other way."

In time, Mark Pimlott hopes, it will become easier for him to work in all the fields that interest him. "But until one’s practice is really established in all its variety," he says, "I think it’s very difficult. I mean, people say, ’Weren’t you the painter last week’?" Yes, in fact, he was. And before that the designer for the disco-garage, and the artist who made those lights under the overpass.