Tracey Emin: Artist over— and in— the broadsheets (2001)

“... the tent and the artist offer great copy generated by the artwork’s contained textual focal points— the artwork’s title, facilitation of a media-genic headline, the description the artwork generates, her brilliant Tracey quotes, and the resultant polarized reactions. In fact, many of her works follow a similar experiential and media path...”

Art Design Publicity at ADC | 26 August 2011

This article was previously published in Parkett, 63, pp. 50-4.

> Click to see Tracey Emin. My bed, (1998) in varied publications, exhibitions

Tracey Emin

I remember that time as if it were yesterday, when I had just moved to the exotic island after living in Southeast Asia. Upon my arrival to London, some were still grieving over their lost princess, while others were all excited about some art show held at a place called the Royal Academy. I wandered into the press preview, started with the shark, but became quickly mesmerized by "the tent." On the floor, peering inside and giggling, a radio journalist walked over and asked to interview me...

This was my introduction to the work of Tracey Emin, and until recently, I had never met the artist. Since the media-hyped exhibition Sensation (1997), I was fascinated by her drunken performance on live national television after Gillian Wearing won the Turner Prize, and I cheered as she stormed off the set. In fact, I so much appreciated her work and enjoyed reading the ever-increasing and multiplying newspaper reports covering, creating, and manipulating her art-and-media persona— Tracey interviewed by David Bowie, Tracey gets drunk, Tracey takes her clothes off, Tracey short-listed for the Turner Prize (1999), Tracey does gin adverts and fashion shows, Tracey takes a shit, Tracey lands on Mars. Absolutely everyone in Britain knows that artist, but Tracey is no longer just an artist— she’s a phenomenon. When I finally interviewed her in her London studio, my head was so fuckin’ dizzy from reading newspaper features about Tracey Tracey Tracey, that it took me ten minutes to focus and gradually discover that I was speaking to a "real" person— who was nice, polite, and serves a good cup of tea. [See the Q&A interview, section C, published in Sculpture magazine.]

Emin, or rather "Tracey," works across a diverse range of media—including drawings, blankets, neons, videos, installation, and sculpture, as well as found and manipulated objects from her personal and professional art life. She appropriates a variety of styles and incorporates them into "Tracey," much in the way that Japan imports things, refines things, and makes them Japanese. Not in an overly studied postmodern sense, but in an expressive manner that so many of the world’s artists pursue, and many art world power holders snub and ignore. Instead, she makes art that makes sense to her, and the artwork she likes, and the movements that influence her, fall beneath that.

Tracey isn’t trapped in the art historical who-did-what-first game[1] for expanding her audience, income, and her art world. Nowadays, she doesn’t need it, as she’s so fabulously beyond it. She’s located her audience, a mass tribe, based on personal and professional commonalities. Don’t we wish that all artists were able to locate their own tribes like Tracey? With her developing media prowess and connections, Emin’s army (1993-97), she reinforces the notion that artists can create their own international networks, instead of a Third-World art hierarchy set up for those who select and define— and those who follow. Tracey emancipates artists by further emphasizing an alternative route, here the media addressed by Jeff Koons and Mark Kostabi. But Tracey the phenomenon has been raised to new media heights, giving fellow Brit Damien Hirst a run for his money.[2] With her strong visual and controversial focal points—in her art, autobiography, personality, and her naturally media-genic communications skills—the result shows the power of her art-artist fusion. Meanwhile, contextually and contentiously in Britain, this results in recasting the personal into art—and her personality into unprecedented mass-media coverage.

The starting point is Tracey pushing Britain’s boundaries of private subjects and explicit autobiography.[3] A half-English, half-Turkish youth having an unusually difficult life, Tracey Emin grew up in the coastal resort of Margate in Southeast England, and her problems continue into adulthood. Art-artist revelations of an angry voice demanded to be heard— being raped at thirteen and suicide attempts referred to in selected drawings and monoprints, a period of sexual consumption afterwards via Why I never became a dancer (video, 1995), and two abortions in How it feels (video, 1996). "I want people to be emotionally manipulated in my shows," she explains. "I want them to laugh sometimes, to smile, to feel sad, and occasionally get angry."

As representations of autobiography and historical facts for the public, her work demonstrates the limitations of anyone’s autobiography in a legalistic sense, accounts in a journalistic sense,[4] the presence and absence of information (or editing), and the fundamental isolation of the individual. As outsiders, we never know where the autobiography is in relation to the language of the art object, the artist’s writings, and mediated media publication, while autobiography incorporates the problems of remembrance. When I ask Tracey about this, she replies, "We all know that truth is different for everyone depending on their perspective. It’s how I see it. For example, with Why I never became a dancer, it’s factual information put into a narrative. The reality was worse—I was being called a slag on the street—not just in the dance hall." I push for more examples; Tracey says, "When I did My major retrospective,[5] some people just didn’t believe any of it." The difficulty in dealing with this kind of work is that when you inquire about the subject, you awkwardly end up putting the artist on the stand; at the same time, it’s hard to maintain distance.

In any event, [the art-autobiography] acts as a vehicle that interacts with viewer’s remembrances, and empathy, or lack of it. Tracey’s art-autobiography sensibility and its resultant media effect were first truly realized with Everyone I ever slept with 1963-1995 (1995).[6] She listed 102 names inside the tent’s container-like form, encouraging the viewer to peer inside to discover the revelations, while intruding into the interior space. With this work, Tracey talks about different levels and kinds of intimacy, both by listing previous sexual partners (those she could remember), as well as her twin brother inside their mother’s womb, and other non-sexual partners.

Everyone...’s effect triggers a predictable range of responses for the individual, with some in her tribe thinking about their own "inventory." However, with the title being a euphemism for sex, the tent and the artist offer great copy generated by the artwork’s contained textual focal points— the artwork’s title, facilitation of a media-genic headline, the description the artwork generates, her brilliant Tracey quotes, and the resultant polarized reactions. In fact, many of her works follow a similar experiential and media path.[7] Although when she was making Everyone..., she said, "I didn’t do it for media sensation. I didn’t have that expectation." Instead she needed to produce a work for a curated group show that needed something physically large, and she was thinking about intimacy levels and AIDS. Everyone... remains a favorite work for Tracey, although she wishes she could delete a few names that she listed, not anticipating the tent’s media might.

In some ways, Tracey’s works on paper are the keystone of her practice, a vehicle for quickly writing her ideas and expressing her visual thoughts in a manner referencing Egon Schiele and German Expressionism. Within this stylistic context, she explores explicitly personal issues like masturbation and sex, her body, being ill and hungover, occasionally animals, and her daily experiences. Meanwhile with her fabric appliqué works, Tracey takes a favored feminist genre and makes chairs, cloth-covered boxes, and most notably blankets, as a platform for image and text. Tracey says, "I have to really love the object— I have to have it a really long time around me." Her autobiography is not only the subject matter, but also the process of sewing, with memories generated in the process. For Tracey, the form itself leads to constructing texts, sometimes stories, poems, or single sentences, sometimes coherent and sometimes contrasting. Why are there several misspellings? Tracey is dyslexic and opts to keep her naturally generated spellings, as opposed to editing them.

Her neons, which recall Mario Merz and Bruce Nauman and contrast with the statements of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, feature roller coaster "girl talk" like Is anal sex legal? (1998) and Fantastic to feel beautiful again (1997) in pink, and My cunt is wet with fear (1998) in white, while Very happy girl (1999) divulges the size of her boyfriend’s penis. She’s fond of neon’s relationship to drawing, as it continuously moves, repeating itself. From the title/artwork/language reactions of her neons, her video installation The interview (1999) leads into its subject; Tracey’s autobiography is transformed into a duel of personality splits with Good Tracey interviewing Bad Tracey, both played by Emin. Good Tracey can no longer tolerate the other’s excesses and walks off the set— a replay of her Turner Prize TV appearance, in reverse?— as her opposition announces "Fuck Off” in triumph. Set on a wooden stage, two small-scale chairs face the monitor, adjacent to little-girl slippers.

But after being nominated for the Turner Prize and the resultant exhibition of the four short-listed artists’ work at the Tate Britain gallery, the media attention got way out of control for Tracey. She became that artist who made that bed—an installation also including stained pillows, cigarette butts, K-Y jelly, empty vodka bottles, used tampons, tissues, and her dirty knickers. The scene depicted utter despair.[8] Her intended viewer reactions were triggered, but Tracey wasn’t resourced enough to deal with and distance herself from celebrity-style media hounding. She reports being door-stepped by journalists and her mother being harassed, during a time that resulted in well over 100 press clippings.[9]

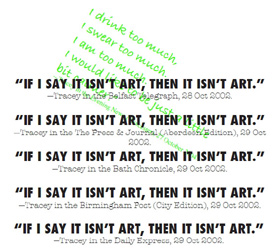

When I asked Tracey what she thought about the current discourse in newspapers on herself and her art, she replied, "I think of it as people paying for their mortgages, and paying for their mistresses, "she smiles devilishly, then grows cold, "writing any old crap about me."[10]

After the Turner Prize media frenzy, Tracey reevaluated her position with the solo exhibition You Forgot to Kiss My Soul (2001), and there’s a marked, "more upbeat shift" in her work, she says. "I thought, ah, fuck it. They’re going to slag me off anyway," she explains. "It doesn’t matter what I make; it doesn’t matter what I do." She continues, "Basically, it’s up to me what I do. And I’ll struggle and fight and do new things to excite myself." This sensibility produced works such as Self-Portrait (2001), inspired by Louise Bourgeois’s towers at Tate Modern (2000) and Tatlin’s model for the Monument to the Third International (1919-20), in a metaphor of her up-and-down life with an autobiographical helter-skelter. Her video The Bailiff (2001), viewed inside a wooden closet, shows Good Tracey/Bad Tracey from The interview in a Shining-like sequel where one Tracey tries to break down the door of the other— frightened and holding scissors.

Tracey’s sensation-led experience continues with The perfect place to grow (2001), a video viewed through a peephole, recalling Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés (1944-66). But instead of sex and violence, a pleasant, smiling older man, her father walks toward the viewer offering a flower. It’s this work which symbolizes what Tracey’s tribe hopes for Tracey— more stability and happy moments. Her tribe also eagerly awaits the next chapter in Tracey’s personal and professional life— via her artwork, her discourse of context and intention— while some are hungry for the next revelation in her multiplying media discourse.

References:

[1] This construction in itself is problematic, given the dynamics of art world power holders and language, interest holders, money, visual arts media and communications, and the presence and absence of, and access to, information about the totality of artistic activity. See Norman Fairclough, Language and Power (London and New York: Longman, 1989); Norman Fairclough, Media Discourse (London and New York: Edward Arnold, 1995); Moi Ali, Copywriting (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997); and David Carrier, Principles of Art History Writing (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991) and his earlier Artwriting (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1987).

[2] In comparison to America, British newspapers and those of the tabloid variety are far more nationally centralized.

[3] Other artists who have worked with explicitly personal subject matter include Carolee Schneemann, Sue Williams, Karen Finley, Kathe Burkhart, Jo Spence, and David Wojnarowicz. With regard to the politics of representation, she’s been accused of "marketing victimology" with her pieces and actions. She’s also been critiqued for presenting work that’s "too literal"— one of her strengths in reaching a larger audience.

[4] See Norman Fairclough, Media Discourse (London and New York: Edward Arnold, 1995). While his examples are often from political discourse, the same principles apply to the variety of genres of art discourse, including that in newspapers, the art press, and academic material.

[5] At Jay Jopling/White Cube (1994).

[6] First exhibited in the exhibition Minky Manky (1995) curated by Carl Freedman.

[7] See R.J. Preece, "Headliner Hotels", Frame, 10, 1999, pp. 52-55, which discusses the media-and-design fusion of Philippe Starck-designed hotels for Ian Schrager. For a detailed case study examining 100 writings, see R.J. Preece, The Problematic Discourse on Philippe Starck’s Delano Hotel, MA dissertation (Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, UCE, United Kingdom, 1999).

[8] In terms of autobiography, My bed’s previous exhibitions in Tokyo and New York (at Lehmann-Maupin) (1998-1999) had a real noose hanging overhead. On the upside, when the piece was presented at the Tate, the noose was removed out of her life, she says, and removed from the artwork.

[9] Future researchers should be warned that the writings on Tracey in totality reflect a discourse in disarray. In addition to hearing account after account of chronic inaccuracies and complete sensational fiction, her assistant recently told me that a newspaper "journalist" threatened to make a story up completely, if he could not interview Emin.

[10] Please note that while Tracey delivers great quotes, they are produced in a context of less sensationalism, which a comparison of a transcript and article would reveal. Also see Norman Fairclough, Media Discourse, concerning the problems of inter-textuality.