Thomas Girst interview: Communicating BMW Art Cars (2009)

Does this unique mix of art, design and publicity offer a blueprint?

Art Design Publicity at ADC | 10 June 2009 | Updated 8 Aug 2012

Co-partner: Sculpture magazine, May 2009 issue. This is an extended version of the excerpts from the interview published in Sculpture, which was shaped by the practicalities of hard copy and word count constraints. These additions are indicated with a grey background.

Thomas Girst interview: Communicating BMW Art Cars

-

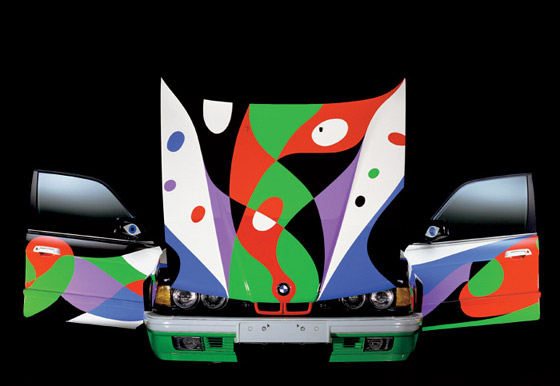

BMW M1 group 4 racing version Art Car by Andy Warhol (1979). This car was co-driven by Frank Stella during the German Formula 1 Grand Prix during the initial laps before the race.

Marriages of brand-name artistic talent and luxury consumer goods don’t get much better than the partnership showcased on a recent summer day in southern Germany. At the Formula 1 Grand Prix racetrack, racing enthusiast Frank Stella was co-driving a [1979] BMW M1 ProCar hand-painted by Andy Warhol. As spectators watched, Warhol’s Pop artwork accelerated into a colorful blur of speed and sound. For the past five years, Thomas Girst has been in charge of all matters concerning BMW’s Art Car project: guiding the commissioning process, coordinating communications and marketing, and scheduling international exhibitions. Girst studied art history at the University of Hamburg and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Later, he worked at a New York gallery specializing in German Expressionism and served as research manager at the nonprofit Art Science Research Laboratory. He has also contributed to German art magazines and national daily newspapers.

The Art Car program began in 1975 with a car painted by Alexander Calder (on view at the Irish Museum of Modern Art through June 21). The collection now includes 16 works by renowned artists, including Stella, David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and most recently, Olafur Eliasson. Created as “rolling sculptures,” the Art Cars are based (when not on tour) at the BMW Museum in Munich. Over the years, they have been exhibited at numerous museums and galleries around the world, including the Louvre and the Guggenheim Museums in New York and Bilbao. Eliasson’s Art Car (not a decorated racecar, but a non-functional artwork) debuted at Munich’s Pinakothek der Moderne in 2007 and was exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art last year. This year, after showings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and New York’s Grand Central Terminal, an installation of BMW Art Cars by Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg is on a three-city museum tour in Mexico.

The following are excerpts of my conversation with Thomas Girst:

R.J. Preece: How did the Art Cars initiative begin?

Thomas Girst: The initial idea came from a French auctioneer named Hervé Poulain, who was also a racetrack driver and very good friends with well-known artists. Poulain asked Alexander Calder to design the exterior of his BMW 3.0 CSL. The car then took part in the 24-hour race in Le Mans. In the ’80s, with the internationalization of the company, our different operating companies in national markets were asking for Art Cars. They were primarily created for individual markets. However, starting with Olafur Eliasson’s car— the 16th in the series— we decided to leave the artist selection to professionals in the art field, including curators from major museums around the world.

R.J. Preece: Over the years, what has been the purpose of the BMW Art Car?

Thomas Girst: It’s changed over time. In the beginning, the cars were raced. There wasn’t much of a public relations effort around them, nor were communications opportunities sought. Since then, some of the Art Cars have been used in advertisements to show that BMW is a player in the arts. With the Olafur Eliasson work, part of what we are doing is raising awareness of alternative and renewable energy sources.

At the same time, BMW sponsors over 100 cultural events each year that have nothing to do with the Art Cars. Most of the things that we sponsor deal with contemporary art, classical music, and design and architecture. It’s rather diverse though, if you look at it from a global perspective. Our sponsorship has included a street festival in Mexico City, a jazz festival in Beirut, and an arts discussion forum in Melbourne. So, some of our sponsorship has been about supporting events to create a platform and an awareness that make certain things possible. It’s been our goal to develop innovative formats that position the company as a corporate citizen. We also aim to show that we are a trustworthy, credible, and authentic player in the arts over the long haul.

R.J. Preece: But there’s a visibility element to this too. It’s not only about being a good corporate citizen, it’s also about communicating being a good corporate citizen, right?

Thomas Girst: Yes, as a company, we are not altruistically involved in the arts, that is for sure. We, of course, want to build up the image: the image of BMW. We want a positive association from our engagement in the arts for the brand as a whole. Over the years, our involvement in blue-chip art fairs like Art Basel Miami Beach, Art Basel, and Frieze London has certainly had an “in your face” approach: we want to be there with our cars, shuttle the VIPs, and thus create visibility, presence, and exposure for our brand within a commercial enterprise.

Working with artists directly or sponsoring cultural institutions is a whole different approach. As much as we love our logo, we wouldn’t want to see it projected “Batman style” onto the red curtain before the Philharmonic Orchestra starts to play. These situations call for subtlety. The audience is highly sophisticated— and while wanting to be recognized, the last thing we want to do is get between art and the spectator.

-

BMW 730i as Art Car by César Manrique (1990).

Thomas Girst (continues): There are various possibilities to structure cultural engagement within a company the size of BMW. First, cultural engagement can be part of a foundation. In this way, there doesn’t have to be a connection to public relations or marketing. Or cultural engagement takes place within the public relations/ communications department, [1] or in the marketing department. [2]

So for the unveiling of the 16th Art Car being shown at the Pinakothek der Moderne museum in Munich, we arranged for over 130 journalists from around the world to be flown to cover the Art Car.

This is part of what we do.

R.J. Preece: What trade presses do the journalists write for? And how did this work?

Thomas Girst: We offered airfare and accommodation for the journalists to see the show in Munich. Basically we informed communications managers in the countries that sell BMW cars about the upcoming event. And they made inquiries to find out which journalists might be interested.

Denmark and Iceland brought a lot of press because Olafur Eliasson is Danish-Icelandic. Overall, what resulted was a combination of art press, automotive press, lifestyle press, newspaper features in different newspaper sections, etc.

Of course, news announcements occurred in several kinds of publications that found what we were doing to be of interest.

Plus Olafur Eliasson’s studio and the museum itself were also interested in certain members of the press being there and we coordinated the invitations together.

R.J. Preece: Why do some people in the art world consider corporate sponsorship and involvement problematic? To me, it’s not an issue. It’s another kind of artistic output, or project, produced in another context.

When you bring anyone or any organization into a project, you have to give something to them to make it worth their time. Everyone’s time is valuable, or should be.

What do you think?

Thomas Girst: Ever since the 18th century, with Immanuel Kant and then Schiller, art has been positioned as autonomous. It’s been positioned as being the opposite of economic thinking, growth, benefits, and profit-making. If we look at the art community today, the defining factor is the art market—for better or worse. Being an artist was a different thing as recently as half a century ago when a handful of galleries showed contemporary art, say, in Manhattan, as opposed to over a thousand nowadays.

The art community is right to question any interference from big money. But I think that, in regard to corporations, one needs to look at which companies are doing it, why they are doing it, and how they are doing it. Personally, I believe it to be less problematic when a company whose core business is not part of the art market sponsors a show, as opposed to galleries, auction houses, or collectors making things happen within museums. I think that the artists should make the decisions they want to make. And the corporations should decide which artists to work with and support.

When I was only working in the art world, I knew about the Art Cars and thought they were the most horrendous mixture of big brand and artists. I thought, “This is just throwing money at artists in order for them to sell cars.” Now, I think very differently— not because I’ve been corporate-brainwashed or because I’m the spokesperson, but because I learned more about the Art Car’s history. Once you get to know that unique history, it becomes clear that the initiative has not been about what critics think.

-

BMW H2R prototype frame as "Art Car" by Olafur Eliasson. Title: Your mobile expectations: BMW H2R project, (2005-07). Stainless steel frame, orange lighting, ice, and BMW H2R prototype frame, placed in an 800-square-foot refrigeration unit.

R.J. Preece: Eliasson’s Art Car marks a visual and conceptual shift in the series, doesn’t it?

Thomas Girst: The break with the series could not be bigger. Olafur Eliasson took apart the H2R car, took out the engine and the chassis, and left the bottom intact. Then he created numerous layers of stainless steel plates and wire. If there were no ice on the plates, the design would quote the original chassis of the racing car, via its form. Underneath he placed subtle orange light. But there are about 2,000 liters of water frozen into ice on the steel plates, which Olafur Eliasson’s studio sculpted into shape. If you bend down and look through, you can see the steering wheel of the car, also covered in ice. The work is ever-changing, and the ice reduces toward the end of the show. Generally speaking, the work reflects themes of mobility, temporality, and renewable energy. It can trigger a dialogue about the relationship between car production and global warming. This is presented in a sophisticated and aesthetically stimulating way. While you obviously can’t drive Olafur Eliasson’s Art Car, it’s based on a prototype that was designed to race on a track and prove that a hydrogen-powered car can go as fast as 300 kilometers/hour. This technology continues to be developed at BMW, and we’ve proven that hydrogen can replace conventional fuels— and still achieve performance.

R.J. Preece: How important was communicating the project?

Thomas Girst: It’s part of why we do this. But as we just discussed, a part of the art world criticizes corporate involvement, and people should note that we take this into account. For example, we wouldn’t run advertisements showcasing Olafur Eliasson’s artwork. First, because that would go against our agreement with the artist. Second, I think that it would go against our ethics to turn the Art Car into a poster child for BMW’s green engagement.

R.J. Preece: (Bursts into laughter).

Thomas Girst: I know. Sometimes when I speak to the press for example, and those solely working or writing in the arts, they start to mention that maybe Olafur Eliasson’s Art Car is a perfect symbol of…

R.J. Preece: A symbol of environmental sustainability. That’s right.

Thomas Girst: And I tell them, Olafur Eliasson’s car isn’t functional as transport. It’s a whole different discussion.

It’s a good discussion, but there are hundreds of engineers working on this problem of carbon emissions. So it’s perhaps better and more direct and appropriate to focus on the real car and the technology, versus Olafur Eliasson’s artistic work.

R.J. Preece: Many companies have been engaged in communicating corporate sustainability recently. Does using Olafur Eliasson’s Art Car as a core communicative element run the risk of looking too opportunistic?

Thomas Girst: I don’t think that the artist would want it. And I don’t think that we should want it either. In order to prove the company’s commitment to sustainability, for example, you need to show how the entire BMW fleet has reduced its carbon emissions over the past 10 years— and the projection for reduction in the next 10 years. In other words, hard facts are more effective, more real— and not a smokescreen created by involvement in art dealing with environmental matters. Also, it’s important to note that Olafur Eliasson’s work requires an 800-square-foot refrigeration unit that must run all of the time. It takes a lot of energy to freeze a car. Of course, he was keen on using green energy to create that climate.

R.J. Preece: With reference to the other cars, I saw a photograph of Andy Warhol painting a car with a brush. But cars are usually sprayed. How does the painting work?

Thomas Girst: The artists usually worked with a professional car painter. Andy Warhol applied a special paint. What’s interesting to me is that he usually had his assistants doing his production for him; but with the car, Warhol took a mass-produced object and painted it himself. Afterwards, he signed the car with his fingers and even fingerprinted it. Some artists worked with models, and then the car painter followed the specifications. But most painted the cars themselves.

R.J. Preece: Art can often be very distant from the general public. Your project has increased visibility for art by placing it on the race track and into auto and technology magazines. Has the BMW Art Car as an artistic medium contributed to other areas?

Thomas Girst: I find it very interesting and unique that the Art Cars have a place outside the art world. They are also something for car enthusiasts and designers. It’s also an opportunity to look at the forms, the product design, of BMW cars. These forms are always changing, based on design and technological developments. Oil on canvas is boring in this regard and never changing. In a hundred years, we will look at 1970s racecars the way we look at horse-drawn carriages today, and our aesthetic take on the BMW Art Cars will shift. I also think that the Art Cars help to bring enthusiasts of art, design, technology, and cars into other spheres where they might not ordinarily go.

R.J. Preece: Do you have a dream for the future of the BMW Art Cars?

Thomas Girst: Right now in Munich, our museum showcases BMW models from the company’s entire history, but we only have room to show one Art Car at a time. So, my dream for the future is never to see a BMW Art Car in storage again. My dream is to see each of the Art Cars on view in different museums around the world.

I don’t know if this will happen, but this is my dream.

BMW Art Cars (1975-2007)

1975 - Alexander Calder - BMW 3.0 CSL

1976 - Frank Stella - BMW 3.0 CSL

1977 - Roy Lichtenstein - BMW 320i Turbo

1979 - Andy Warhol - BMW M1 group 4 racing version

1982 - Ernst Fuchs - BMW 635 CSi

1986 - Robert Rauschenberg - BMW 635 CSi

1989 - Ken Done - BMW M3 Group A

1989 - Michael Nelson Jagamarra - BMW M3

1990 - Matazo Kayama - BMW 535i

1990 - César Manrique - BMW 730i

1991 - A. R. Penck - BMW Z1

1991 - Esther Mahlangu - BMW 525i

1992 - Sandro Chia - BMW M3 GTR

1995 - David Hockney - BMW 850 CSi

1999 - Jenny Holzer - BMW V12 LMR

2007 - Olafur Eliasson - BMW H2R

References:

[1] Communications is of course part of every artistic practice. However, the level of communication varies from the artist communicating to just one person—and extends out to the diverse, multiple media coverage outputs of an art practice like Damien Hirst’s. Only the secret artwork, hidden, and only known to the artist, is "not communicated"…

[2] Some readers might recall the BMW television advertisement in South Africa, but communicated internationally, that featured the large-scale animal sculptures created by Theo Jansen. The wind on a Dutch beach activated them into motion. This presentation was organized by BMW’s marketing department.